It is a bizarre dichotomy , I have seen the meekest of men that will draw no attention as if they were invisible perform like a super hero making me question myself could I have done that. I know exactly what you mean.Funny how that works out. Almost as though courage and cowardice were physical endowments, not acts of will. I've seen it go both ways. Some bland nonentity in the back of the pack who, in a crisis, rises to the occasion with utter grace and confidence like he'd been doing it all his life. And then, the most-likely-to-succeed guy who, in a crisis, goes all to pieces. You never know until you're tested.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

How do you calm yourself in high pressure?

- Thread starter The Exile

- Start date

- Status

-

Not open for further replies.

berettaprofessor

Member

Patrick McManus said it best; one is either a panicker or not. If you are, it's best to get the panicking over with and then get on with it. But I agree with others....the more stressful situations you work yourself through, the better it gets. I'm a surgeon, and over the years have had to control my panics enough that now I can drive people crazy in a crisis because I slip into slow deliberate mode...calm, reasoning, careful. In an emergency, whoever takes the lead has to be the calmest person in the room...yet it so seldom happens.

benEzra

Moderator Emeritus

I would suggest that the best way is to acclimate to it...the more you do it, the more routine it becomes, and the more used to it you get. The first time I shot a local match, I was very intimidated by it and didn’t do well at all, but it was fulfilling and enjoyable nonetheless. You might consider attending a couple of matches as a spectator first, walking around with the shooters to get the feel of how it works, get familiar with the rules and procedures, and become acclimated to the environment. Then the first match you shoot, concentrate on shooting accurately and following the procedures properly, and let speed come later.I have this really bad habit of getting really shaky in the hands when I feel like something really matters, normally it shows up in video games where I really have to give it my all or lose, but I've been thinking about trying to get out for some competition shooting in the future just to try it out but I've always dreaded this scenario I keep imagining where I know that I gotta aim good with every fraction of a second effecting my score and the pressure gets to me, my shots go wide and as I panic to get hits I get worse and worse; and I can just imagine that really getting to me and making me not want to come back for a second try, no one likes feeling like they fumbled at the ten yard line. Is there anything I can try to just keep my nerves under control when the chips are down? Some kind of exercises I can go through at the range or is was I just born with a really bad 'cool' factor?

Obturation

Member

Breathe. Relax in spite of chaos. Spend time learning to clear your mind and it will help. Then train your hand to do what you need to. There is no substitute for experience in chaos and it sounds cliche but don't be afraid. Fear will get you hurt or lead to failure. Don't try to be superman but let your fortitude and strength be more than any opponent can overcome. Your mind is the weapon, it can work for you or against you.

Hangingrock

Member

Previous military and occasional under ground mining experiences (not for the faint of heart).

JTHunter

Member

What about "primal screaming"? A roaring scream at the top of your lungs (think of the Hulk reviving Iron Man in the first "Avengers" movie). It also startles the hell out of everybody around you and causes everybody to freeze in disbelief for a few seconds.

What about "primal screaming"? A roaring scream at the top of your lungs (think of the Hulk reviving Iron Man in the first "Avengers" movie). It also startles the hell out of everybody around you and causes everybody to freeze in disbelief for a few seconds.waterhouse

Member

Training in high stress situations, which has taught me that what works really well for me is a concentrated deep breath or two. Other methods work well for others.

Corpral_Agarn

Member

I really like this post.In Jim Cirillo's book he talks about the stakeout squad and choosing members for it. Trying to find people who would perform well under pressure was key but there wasn't a good recipe for it--so they came up with one.

Remember, this wasn't a list of things to DO in order to be on the squad, this is a list of things they looked for in candidates. So clearly he wasn't saying that people should go out and get married and have kids to be able to perform better under pressure, only noting that they believed that picking people with these characteristics helped insure they got people who could perform well under the extreme pressure of a gunfight.

Here's the list from Cirillo's book "Guns, Bullets and Gunfights". You can draw your own conclusions. Note that although it is presented as an 8 item list, as in the book, there are actually 12 questions. He said that 7 'yes' answers was good, 'yes' to everything was better. He also said that even with a good "score", 2 hours of training per week under time limits and pressure with someone else scoring/monitoring/setting up unknown challenges was a necessity.

1. Are you a competitive shooter?

2. Have you competed in major matches and placed and won awards?

3. Can you perform well under pressure or fear?

4. Are you a hunter? Have you shot big game?

5. Do you like outdoor physical sports?

6. Do you collect firearms? Do you reload ammo?

7. If you are over 28, are you married? Do you have children?

8. Do you like people? Do you attend civic affairs?

My 2 cents.

It's easier to be calm when things are crazy if:

1. You have the skills to deal with the problems and those skills can be applied without having to think through each step of the process. Imagine trying to avoid a car accident if you have to think: "There's an object in front to the right. Ok, move right foot from accelerator to brake and press down. Move right hand upward and left hand downward to steer to the left." You'd never make it. You need to be able to react without having to think through each of the steps in the process.

2. You have a plan to deal with the situation--this also involves being AWARE of the situation so you know what plan to implement. I'm not talking about a detailed plan with a step-by-step process, I'm talking about having considered various possibilities in advance and come up with some general ideas on how to react. This is very simple and very important. Imagine driving down a road on a dark night and seeing something at the last minute in front of you. Do you want to spend time trying to figure out if it's a large piece of cardboard or a large piece of steel so you can then decide if you should try to avoid it or not? No, there's no time for that. Decide in advance that you will ALWAYS avoid hitting unknown objects of significant size if you can do so safely and that if you can't, just slow down as much as you can before impact. This also means being aware of the situation--seeing the object, knowing whether or not you can swerve into the lane next to you without hitting another vehicle, so that's why situational awareness comes in on this point.

3. You have the knowledge necessary to make good decisions. If you can immediately start applying your knowledge and see that it's applicable, you won't have time to let your mind start telling you that "all is lost, time to run in circles, screaming and shouting".

4. You don't waste time aligning your mindset to reality. If you stand there telling yourself that you can't believe it's really happening to you, you are wasting time you may not have. That puts you farther behind the curve and it also is not a productive mindset. You need to immediately assess and start working through your toolkit to see what you have that is applicable to the problem you need to solve. The quicker you start doing something constructive, the less likely you are to panic.

5. You maintain a "can do" attitude. If you "internally give up" that puts you at a serious disadvantage and makes it much harder for you to work through the problem. Once you start thinking you can't get it done, you're more likely to panic.

I came to post something similar.

I think Panic/Fear comes from a few different sources:

1. You don't know what is happening

2. You don't know what to do about what is happening

3. You don't think that what you can do will effect the outcome enough to make a difference

IMO this is why training is so important. Even simple things like a Stop the Bleed course can save lives.

Training helps us recognize what is happening.

Training teaches us what to do and gives us a course of action. The time to figure out what to do is long before you need to do it.

As for the feeling of helplessness... where you are unconvinced that what you can do will effect the outcome... That comes from experience, practice, a large dose of resolve and...

the simple understanding that you can do everything right and still lose.

I only have my own experiences to go on, but for whatever reason, I have found myself in emergency situations more than a few times. Horses, snowmobiles, random accidents (office, ranch, just walking down the street), spending a lot of time in the woods, etc... a lot of times it means you are the first responder.

I have to say that the medical training I received in my Boy Scout troop has saved more than a few lives.

OP, for competitive shooting, remember the stakes: None.

The cardboard isn't shooting back. The worst that could happen if you are slow or inaccurate is you place last. Oh well!

That's the place to see where you stand.

Stay focused on the safety and the rest will come with practice/experience.

Stress inoculation training. Competitive shooting is great but it doesn't really place you under the same kind of stress a deadly force encounter will. There is a reason the military uses things like the high obstacles on the confidence course (note that it's called the confidence course and not the obstacle course). The Army uses training events like the confidence course, the 200 foot night rappel in Ranger School, the stress exercises in the pool in the combat diver course etc. There is very little call for a SWAT team to rappel down the side of a building to make a dynamic entry, yet rope work is (or was when I went through) most SWAT, Emergency Service Team training. Why to put people in a position where they are actually in fear for their life in a controlled environment so they can learn to deal with the fear

I really like this post.

IMO this is why training is so important. Even simple things like a Stop the Bleed course can save lives.

Training helps us recognize what is happening.

Training teaches us what to do and gives us a course of action. The time to figure out what to do is long before you need to do it.

At my FD, we say that under stress, you fall to the level of your training. So the more you train, the better you do under stress. Yes, some people deal with stress better than others, but in the end it seems the training and experience is a major factor.

Quite frankly, if playing a video game induces this much anxiety you'd do best to join either a nunnery or order of monks, depending on your sex. But I know for many today the most stressful thing in their life is a video game, so I guess that idea is out.

There isn't a magic trick to overcoming your response to stress. But you can develop ways to use it. Some say yoga or meditation help. Personally, I'd just try finding an activity that induces as much stress as possible and learn how to adapt.

There isn't a magic trick to overcoming your response to stress. But you can develop ways to use it. Some say yoga or meditation help. Personally, I'd just try finding an activity that induces as much stress as possible and learn how to adapt.

George P

member

- Joined

- Jan 10, 2018

- Messages

- 7,772

Everything that everyone in this thread has said about training sounds like good, solid advice to me. Beyond that, I would add that some people (maybe Jim Cirillo, for example) are just good under pressure. For example, when you are at 35,000 feet, and three of the four engines are on fire, some people look at that and become more calm. They relax. They concentrate. Their minds become clear and focused. Those are the guys you want flying the plane.

I apologize if I am stating the obvious.

Or, it could be because they are praying and saying their last rites......

CapnMac

Member

There's no end of homilies and hoary old adages that can guide here.

"Practice makes Perfect" would be one.

"How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice."

"Train hard; Fight easy"

@Corpral_Agarn hit on this, make the unfamiliar the familiar, an the stress of the new, the foreign, the alien is reduced. How to cope with multiple stressors--usually one at a time; which is entirely down to practice.

As with all things human, there is a spectrum: Some are better and some are worse. But, typically, none are hopelessly mired along that spectrum, unless they fail to change.

Some of it is just down to grit. And practicing that grit. When you feel like you have to quit, and can go no further--just don't, keep moving, keep going.

"Practice makes Perfect" would be one.

"How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice."

"Train hard; Fight easy"

@Corpral_Agarn hit on this, make the unfamiliar the familiar, an the stress of the new, the foreign, the alien is reduced. How to cope with multiple stressors--usually one at a time; which is entirely down to practice.

As with all things human, there is a spectrum: Some are better and some are worse. But, typically, none are hopelessly mired along that spectrum, unless they fail to change.

Some of it is just down to grit. And practicing that grit. When you feel like you have to quit, and can go no further--just don't, keep moving, keep going.

243winxb

Member

https://www.bullseyepistol.com/ Get in the zone.

jmorris

Member

- Joined

- Sep 30, 2005

- Messages

- 24,232

It's not really adrenaline I think, more like nerves fueled by my ego if that makes sense. I know I can do better, and I know I look like a screw up to a lot of people.

First thing I would do is knock off the negative self talk, that just makes things worse. Flip that around to “Next time, I will...” or “I’ve got them if they let their guard down after that stage.”

Very important is once a stage or game is over, its over. If you are still playing the last one in your head (good or especially bad) vs the next one you are wasting what room you have in your head.

Acclimatization would be helpful but you have to be there to do that and don’t allow it to turn into complacency.

Read “With Winning In Mind” by Lanny Bassham.

Last edited:

Howland937

Member

I have trouble relating to pressure from competing at video games, but it's probably not much different than any other competition in that a large part is mental. I used to shoot pool a lot and like most people, bet on my abilities often. Lots of nights I didn't pay for a single drink, but put a $10 bill on the game and I suddenly became terrible.

Obviously, there's a talent disparity between pros and amateurs in any field. When someone says their training "kicked in", they're saying that they've trained to the point that it's a reaction as natural as breathing. But the training does need to simulate real world scenarios that you may encounter.

BTW, if your performance on video games gives you negative thoughts about how you'd handle a real life problem, maybe consider putting the controller down. Especially if it gets you that worked up. Can't be good for ya.

Obviously, there's a talent disparity between pros and amateurs in any field. When someone says their training "kicked in", they're saying that they've trained to the point that it's a reaction as natural as breathing. But the training does need to simulate real world scenarios that you may encounter.

BTW, if your performance on video games gives you negative thoughts about how you'd handle a real life problem, maybe consider putting the controller down. Especially if it gets you that worked up. Can't be good for ya.

@FL-NC gives the answer I can most identify with. Going through harrowing stuff in the military isn't about not being scared; it's about being scared, but knowing yourself, your skillset, and your teammates well enough to perform anyway.

Adapting that to a civilian who's starting from scratch, here's what I would recommend:

1) Learn to fight. Start with something unarmed. Krav Maga and Jiu Jitsu are the fighting styles I've had some contact with that I thought were practical. They left me feeling like I would be better able to handle myself if the deal went down.

2) Get in shape, and stay in shape. You don't have to be a nationally ranked crossfit athlete nor an ironman if it's not your thing, but if you know you have the strength and stamina to be an asset to yourself and your loved ones if needed, that goes a long way to instilling confidence.

3) Compete. Test those skills. Fight in tournaments, run races, do a triathlon. Do something to raise the stakes, test yourself, and add a little more stress to see where your capabilities lie.

4) Mental components. The right answer varies greatly from person to person here. It could involve spiritual fitness like religion and/or meditation. It could involve knowing your lizard brain, and being able to throw a switch internally where you will win or die trying. It could involve visualization. Breathing exercises. I highly recommend the Michael Jordan documentary The Last Dance on Netflix for a look at what a win-at-all-costs mindset can be. One of Jordan's secrets was always being in the moment, and always being angry. That first part makes it easier to go on when you miss a shot or are behind in the game -- doesn't matter, what matters is what you're doing right here, right now.

This is not to say Jordan should be emulated, but to give you a look at how that mindset can manifest for someone at the highest level.

Then, start doing those things with guns. Learn, train, get your skillset in shape, and compete.

Adapting that to a civilian who's starting from scratch, here's what I would recommend:

1) Learn to fight. Start with something unarmed. Krav Maga and Jiu Jitsu are the fighting styles I've had some contact with that I thought were practical. They left me feeling like I would be better able to handle myself if the deal went down.

2) Get in shape, and stay in shape. You don't have to be a nationally ranked crossfit athlete nor an ironman if it's not your thing, but if you know you have the strength and stamina to be an asset to yourself and your loved ones if needed, that goes a long way to instilling confidence.

3) Compete. Test those skills. Fight in tournaments, run races, do a triathlon. Do something to raise the stakes, test yourself, and add a little more stress to see where your capabilities lie.

4) Mental components. The right answer varies greatly from person to person here. It could involve spiritual fitness like religion and/or meditation. It could involve knowing your lizard brain, and being able to throw a switch internally where you will win or die trying. It could involve visualization. Breathing exercises. I highly recommend the Michael Jordan documentary The Last Dance on Netflix for a look at what a win-at-all-costs mindset can be. One of Jordan's secrets was always being in the moment, and always being angry. That first part makes it easier to go on when you miss a shot or are behind in the game -- doesn't matter, what matters is what you're doing right here, right now.

This is not to say Jordan should be emulated, but to give you a look at how that mindset can manifest for someone at the highest level.

Then, start doing those things with guns. Learn, train, get your skillset in shape, and compete.

Or, it could be because they are praying and saying their last rites......

It's both, IME. Once you've confronted death on a deployment or in an oncologist's office, you know it's coming. The rest of our society keeps a veneer that leaves death out of sight and mind for many folks. But if you've gotten to peace with the inevitable, it's much easier to perform under pressure and ease into a hyper-focused flow state.

After living part of my life as an adrenaline junkie it's east to stay relaxed in any high pressure situation.

I fact I act & think better in those situations. I'm the type that doesn't like the slow life, if I'm not flying down a track at 100 mph, or taking a tight turn on dirt at 80 mph with the tires squealing, life is just boring. If I have to stop & think about what I'm doing that will make me nervous.

This is where practice come to play, if you have gone through the motions many times it's just muscle memory after that.

I think when I first realized I could do that was in my street car going down the highway, I hit a patch of ice yes I was going fast. But I did a full spin corrected & brought it out of the spin & stayed in the same lane. I did it all without thinking about doing it, my body was so used to feeling that it just took over & did the right thing.

Now I get the same thing hunting. When the buck steps out I say calm & move slow until after I take my shot, then I get nerved up. It has to do with adrenaline control, some can do it some can't.

I fact I act & think better in those situations. I'm the type that doesn't like the slow life, if I'm not flying down a track at 100 mph, or taking a tight turn on dirt at 80 mph with the tires squealing, life is just boring. If I have to stop & think about what I'm doing that will make me nervous.

This is where practice come to play, if you have gone through the motions many times it's just muscle memory after that.

I think when I first realized I could do that was in my street car going down the highway, I hit a patch of ice yes I was going fast. But I did a full spin corrected & brought it out of the spin & stayed in the same lane. I did it all without thinking about doing it, my body was so used to feeling that it just took over & did the right thing.

Now I get the same thing hunting. When the buck steps out I say calm & move slow until after I take my shot, then I get nerved up. It has to do with adrenaline control, some can do it some can't.

Archie

Member

The biggest factor I use and can suggest is to concentrate on the solution to the problem, not what might happen. It depends on the problem. But it applies to all manner of problems.

Remember to breathe.

Remember to breathe.

George P

member

- Joined

- Jan 10, 2018

- Messages

- 7,772

Yep, deep slow breathing; control what you can of the situationThe biggest factor I use and can suggest is to concentrate on the solution to the problem, not what might happen. It depends on the problem. But it applies to all manner of problems.

Remember to breathe.

theotherwaldo

Member

I've always figured that your ability to keep it together while under pressure depends on your base mental state.

My base state is calm, neutral and slightly amused.

I gained this state not long after I was informed that I had just a few years of mobility before my health would deteriorate and I would die.

I was almost six years old.

That was fifty-eight years ago, so I guess that their diagnosis was a bit off.

Anyway, the philosophy that I developed as a result has stood me in good stead. I tend to be amused, or at worst slightly annoyed, when those around me are in full panic mode. This has seen me (and those around me) through wild animal attacks, major industrial accidents, medical emergencies, gang-banger confrontations, house and forest fires, riots and many other situations.

I suspect that my condition is possibly a form of PTSD... .

My base state is calm, neutral and slightly amused.

I gained this state not long after I was informed that I had just a few years of mobility before my health would deteriorate and I would die.

I was almost six years old.

That was fifty-eight years ago, so I guess that their diagnosis was a bit off.

Anyway, the philosophy that I developed as a result has stood me in good stead. I tend to be amused, or at worst slightly annoyed, when those around me are in full panic mode. This has seen me (and those around me) through wild animal attacks, major industrial accidents, medical emergencies, gang-banger confrontations, house and forest fires, riots and many other situations.

I suspect that my condition is possibly a form of PTSD... .

There is a lot going on in this thread, but I will add what I know in the most general terms possible:

desensitization and counter-conditioning

In over-simplified terms, desensitization is training that routinely subjects the trainee to the stress-inducing, nerve-wracking stimulus without a harmful outcome. Essentially, you get used to "it" or something close to it. You learn to cope. It's up to the trainer to design desensitization based on the stimulus that is the potential problem.

Counter-conditioning involves training where the stimulus that might ordinarily signal a harmful outcome results in a reward. It is not the same as behaviorism's positive reinforcement, but rather it is about changing the meaning of the signal. If a signal indicates something that induces stress, nervousness or fear, it can be re-associated with something else, something better.

These two principles can be applied to a lot of different scenarios, whether it's competition, public-speaking, military operations, or what I think is most relevant to this section of the forum: lethal force encounters. However, I don't think it is beneficial to strive to become "calm" in situations that call for more than that. I understand the need to avoid total mental failure, but in many of these types of situations a person can benefit from some adrenaline, from being on edge, and from heightened nerves.

If you're nervous in public speaking, that's good, because it means you care. We've all seen an example of a sports celebrity that just didn't give a f--- anymore. People envy their success, but when the high-achiever stops caring, people just resent them. If you ever get caught up in a lethal force confrontation like a bank robbery, a carjacking, or home invasion, I hope you care and that it puts you on edge. You might start shaking and get that muscle tension dysphonia that makes your voice sound like a little girl. You might not look or sound "cool" like Samuel L Jackson or Elvis, but importantly, you give a damn. It is, after-all, giving a damn that will result in you taking the action that makes a difference.

desensitization and counter-conditioning

In over-simplified terms, desensitization is training that routinely subjects the trainee to the stress-inducing, nerve-wracking stimulus without a harmful outcome. Essentially, you get used to "it" or something close to it. You learn to cope. It's up to the trainer to design desensitization based on the stimulus that is the potential problem.

Counter-conditioning involves training where the stimulus that might ordinarily signal a harmful outcome results in a reward. It is not the same as behaviorism's positive reinforcement, but rather it is about changing the meaning of the signal. If a signal indicates something that induces stress, nervousness or fear, it can be re-associated with something else, something better.

These two principles can be applied to a lot of different scenarios, whether it's competition, public-speaking, military operations, or what I think is most relevant to this section of the forum: lethal force encounters. However, I don't think it is beneficial to strive to become "calm" in situations that call for more than that. I understand the need to avoid total mental failure, but in many of these types of situations a person can benefit from some adrenaline, from being on edge, and from heightened nerves.

If you're nervous in public speaking, that's good, because it means you care. We've all seen an example of a sports celebrity that just didn't give a f--- anymore. People envy their success, but when the high-achiever stops caring, people just resent them. If you ever get caught up in a lethal force confrontation like a bank robbery, a carjacking, or home invasion, I hope you care and that it puts you on edge. You might start shaking and get that muscle tension dysphonia that makes your voice sound like a little girl. You might not look or sound "cool" like Samuel L Jackson or Elvis, but importantly, you give a damn. It is, after-all, giving a damn that will result in you taking the action that makes a difference.

Olon

Member

I have this really bad habit of getting really shaky in the hands when I feel like something really matters, normally it shows up in video games where I really have to give it my all or lose, but I've been thinking about trying to get out for some competition shooting in the future just to try it out but I've always dreaded this scenario I keep imagining where I know that I gotta aim good with every fraction of a second effecting my score and the pressure gets to me, my shots go wide and as I panic to get hits I get worse and worse; and I can just imagine that really getting to me and making me not want to come back for a second try, no one likes feeling like they fumbled at the ten yard line. Is there anything I can try to just keep my nerves under control when the chips are down? Some kind of exercises I can go through at the range or is was I just born with a really bad 'cool' factor?

Not trying to be crass but it sounds like your problem is mental toughness.

When I was a freshman in HS running track and cross country I would get hellishly anxious over races because in my mind my performance was linked with my worth and my identity. My mouth would get dry, I would feel scared and my performance would suck. I'd start feeling sorry for myself in races and do way worse than I did in training runs. Once I learned to evaluate myself based on the input and not the output I got a lot better. A bad race doesn't make a bad athlete; a bad attitude makes a bad athlete. It carries over into everyday life too. I can deal with stressful and new situations by focusing on what I can control and letting the chips fall where they may. People who are described as cool headed are the ones that can be thrown into any given fustercluck and not lose their poise because they know they only ought to worry about the things they can control. If you're nervous about shooting a comp because you don't want the end result to be bad, there's a lot in there that's not in your control. What you can do is rest confidently in your training and let it take over. No last minute prep is gonna help you just like I couldn't whip myself into better shape at the start line. If you do bad you ought to reflect on any errors you made and chalk it up to a step in the right direction.

There's a certain stoicism and poise that comes with building your mental toughness and it comes from grinding through uncomfortable situations until it's not a big deal. That's my take on it anyway.

Phaedrus/69

Member

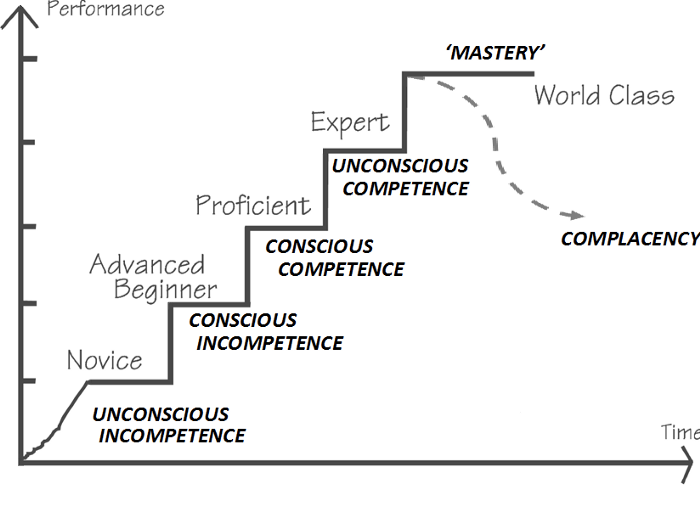

Character has zero do to with it, that much I know. There are plenty of dirtbag criminals that are cool as a cucumber under pressure. It comes down to stress inoculation and skill/familiarity in my experience. The first time you do something you're usually nervous; you don't have any experience so you don't really know if you've learned the skill and you have no way to know but to try it. The more you use a given skill the more comfortable you are, and you move through the stages from unconscious incompetence to unconscious mastery.

Personality is complicated but yeah, the "thermostat" for stress and panic is set at a different level for each of us. Still this is the default setting and it need not remain at that setting your whole life. Some folks are ground down over the years and lose that youthful cockiness while others apply themselves diligently and find they naturally become confident under stress.

The interesting thing is that your body doesn't understand stress in a rational way. Stress due to being in a gunfight is same to your body as stress at giving a speech in front of a large crowd. Long term stress is very damaging to your health (particularly your heart) and it doesn't matter what the source of the stress is.

When I was a young line cook and we'd 300 covers in a couple of hours I'd panic! But after decades as a chef I'm not cool as the other side of my pillow when we're in the weeds. That came from many years of slashing and burning is some very high volume and high end restaurants. The point is that you will learn to deal with stress by training for the situation that's stressing you out.

Personality is complicated but yeah, the "thermostat" for stress and panic is set at a different level for each of us. Still this is the default setting and it need not remain at that setting your whole life. Some folks are ground down over the years and lose that youthful cockiness while others apply themselves diligently and find they naturally become confident under stress.

The interesting thing is that your body doesn't understand stress in a rational way. Stress due to being in a gunfight is same to your body as stress at giving a speech in front of a large crowd. Long term stress is very damaging to your health (particularly your heart) and it doesn't matter what the source of the stress is.

When I was a young line cook and we'd 300 covers in a couple of hours I'd panic! But after decades as a chef I'm not cool as the other side of my pillow when we're in the weeds. That came from many years of slashing and burning is some very high volume and high end restaurants. The point is that you will learn to deal with stress by training for the situation that's stressing you out.

Good Ol' Boy

Member

Lots of good responses. Now I'll give my .02.

I go to work daily working around commercial woodworking machines that can kill you in the blink of an eye. I don't say that to present myself in any certain manner one way or the other.

When you first start working with these machines you are nervous to say the least. As you learn you become comfortable working with them. Not complacent but comfortable. There is a difference.

I'm not an expert but I would be willing to bet its the same for a lot of trades as well as military and LE. Practice and training are of the utmost importance.

That being said, I am also a competitive shooter and religiously shoot 5 IDPA matches a month. I also practice at home both live and dry fire.

Point being im around a lot of dangerous stuff that can get one nervous regularly. The regular part of it is what makes one more comfortable with it.

In regards to competition you just need to go try it. Theres really no other way to get familiar.

As far as keeping your cool in a SD situation there's no real answer for that, except maybe from folks who have been in that scenario.

I go to work daily working around commercial woodworking machines that can kill you in the blink of an eye. I don't say that to present myself in any certain manner one way or the other.

When you first start working with these machines you are nervous to say the least. As you learn you become comfortable working with them. Not complacent but comfortable. There is a difference.

I'm not an expert but I would be willing to bet its the same for a lot of trades as well as military and LE. Practice and training are of the utmost importance.

That being said, I am also a competitive shooter and religiously shoot 5 IDPA matches a month. I also practice at home both live and dry fire.

Point being im around a lot of dangerous stuff that can get one nervous regularly. The regular part of it is what makes one more comfortable with it.

In regards to competition you just need to go try it. Theres really no other way to get familiar.

As far as keeping your cool in a SD situation there's no real answer for that, except maybe from folks who have been in that scenario.

- Status

-

Not open for further replies.

Similar threads

D

- Replies

- 39

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 26

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 66

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 14

- Views

- 584

- Replies

- 59

- Views

- 4K